Not too long ago, Scott McCloud posted in his blog praising a webcomic (not ours, don’t get excited…) for accomplishing a very simple, very crucial task:

“It makes me wonder, on nearly every page, what’s going to happen next.

Simple as that. A little thing, really. And yet, in the end, it’s everything.”

It’s absolutely true to point out, and from day 1 of Zombie Ranch I’ve always tried to achieve that goal. But as with all “simple” aspects of the creative arts, it’s not quite as easy as it sounds.

Zombie Ranch, and the comic McCloud specifically singled out, The Lay of the Lacrymer, both belong to a category of webcomics known as “long form”. The definition of this category can get fuzzy — you could argue the term comes from the fact that you’d usually need to scroll your browser window in order to read it, as opposed to a “strip” webcomic like PVP that fits neatly into a standard screen resolution (this, of course, predates the explosion of mobile devices). You could also argue that it represents a webcomic dedicated to a longer, more dramatic story continuity rather than getting to comedy punchlines. Either way, there’s a lot of bleedover since PVP has had ongoing storylines, and Questionable Content often ends on a punchline even though you’ve got to travel downwards to get there.

If you held a gun to my head and asked me to define it, then I suppose I’d say that at its core, the long form webcomic is definitely more dependent on “What happens next?”, no matter what actual structure it takes. Rather than being a self-contained chuckle, like Lucy convincing Charlie Brown to once again make a doomed run at the football, the long form wants to pull the reader along to the future, to thinking beyond the immediate. And that’s where it starts to get complicated, because long form webcomics also tend to have a slower update schedule. That means you not only want to keep luring the reader along with the promise of more, but you also want to balance that with enough immediate satisfaction to tide them over until next time.

Even with a non-strip format that allows for more than three or four small panels at a time, that’s not an easy tightrope to walk. It’s a special style of storytelling you can’t learn from reading standard print comics (which have several immediate pages to spread the tale across) or gag-a-day offerings (which often don’t need to bother with long-term continuity). Where do you find inspiration, beyond that of the last ten years or so? What ‘masters’ can you study, the way humor strip authors can pore over the works of a Schulz, Kelly, or Watterson?

The answer suddenly came to me, and oddly enough it was courtesy of all the parts of the newspaper comics page I ignored and skipped over when I was a little kid. The long form community does have its legacy, its ancestry, and its masters of the art. Hearken back, friends and neighbors, and remember (or perhaps, if you’re young enough, be introduced to!) the dramatic serial.

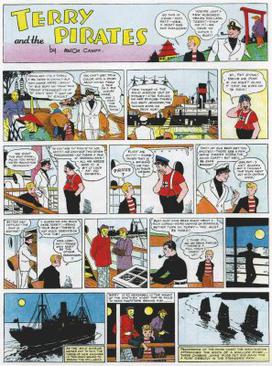

The above is from the famous newspaper comic Terry and the Pirates by Milton Caniff, and you can instantly see a familiar structure to it. If you want to read a higher resolution example in the same vein, here’s one from Frank Robbins’s comic Johnny Hazard: LINK. Other classic serials include Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant, Georges Rémi’s The Adventures of Tintin, or Lee Falk’s The Phantom, all very successful efforts that made their creators (and creations) justly famous. No forced punchlines necessary; they pulled their audiences into their worlds and kept them eager for more, while still delivering a satisfying immediate installment — oftentimes only having the same three or four panel space to work with as a gag strip! I’ve read collections of those tiny daily strips where they’ve been put together sequentially, and somehow they work just as well when viewed all at once, merging into a larger arc. Let me tell you, if you’re working with long form, you will have lasting respect for a person who can manage that, especially when the first panel of each strip often had to be pure recap in case a reader didn’t check the comics section of their paper until Wednesday. Us web guys are spoiled by comparison, with our immediately accessible archives that let a reader catch up just by virtue of a few clicks.

With just a few panels, these masters could hook someone for an entire day. With a larger Sunday offering, an entire week. Worlds blossomed forth. Characters appeared, developed, lived, loved, and even died. World-shaking epics were carved out, piece by piece, in the tiniest of installments, and thousands if not millions of readers were swept along for the ride.

The Web has arguably replaced (or is well in the process of replacing) the printed newspaper in every aspect, including the presentation of comics — which may no longer be crammed together on the same few pages, but are still sought after by an audience craving their unique style of entertainment. And when you realize that, you realize that all those comics taking up the newspaper page had a spread of different things to offer to different people. So for anyone who tells you that long form has no place on the Internet, ask them: didn’t it have its place in print? Have people truly changed so much that all those fans of Steve Canyon, or even a slice-of-life offering like Mary Worth, no longer have room in their hearts for anything that doesn’t wrap up its plotline in a few days at most? That no webcomic is worthwhile if the last panel doesn’t deliver a laugh started in the first? I, for one, say thee nay.

By the way, I fully feel that a gag strip requires its own kind of artistry every bit as demanding as that of a long form. Neither should be sold short, even if the end result might seem so easily digestible. That’s my message to readers. To fellow creators of long form webcomics, the message is to keep striving for that wonderful balance between the immediate and the future, the big picture and the small. And if you ever need help or inspiration, go check out those classic serials: there are some giant shoulders there ready and waiting for you to stand on.

2 thoughts on “Ancestry of the “long form”: the serial thrillers”

Comments are closed.