Cart

Product categories

Support Us!

If you like what I do please support us on Ko-fi or Patreon.

Follow Us!

Join Our Newsletter!

Vote For Us!

Login

Polls

Events

-

Pasadena Comic Con

Dates: May 24

Location: Pasadena Convention Center, 300 E Green St, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA ( MAP)Details:We will be at the Pasadena Comic Con on January 26th. See some of you there for this one day event!

Purchase tickets online at here: https://www.tixr.com/groups/pcc/events/pasadenacomiccon-pasadena-comic-con-2025-115248

-

San Diego Comic Con: SP-N7

Dates: Jul 23 - 27

Location: San Diego Convention Center, 111 Harbor Dr, San Diego, CA 92101, USA ( MAP)Details:Clint & Dawn Wolf will be at San Diego Comic Con, as Lab Reject Studios. We will be at booth N7 in Small Press.

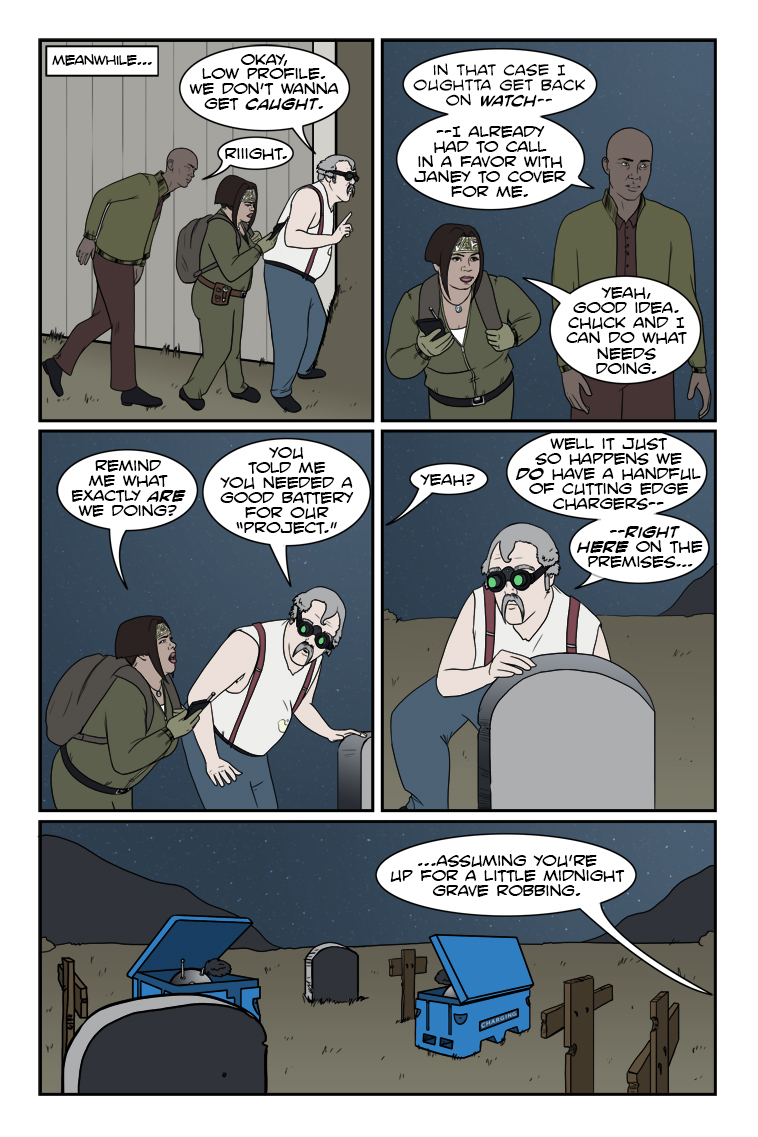

6 thoughts on “541 – Graverobbers”

Crazyman

“Oh, *that* kind of grave robbing? Lead on, Chuck!” 😈

Dr. Norman (not a real doctor)

What? I say “What”?

Keith

Heh, this is going to be fun. Tradition says you need to drink at least one bottle of MD 20/20 before going to the graveyard.

Honzinator

At first I was thinking of something like a potato battery … nope!

Scarsdale

If you take a dead “D” cell battery, take out the carbon rod from the center, cut a strip of galvanized sheet metal about an inch (2.7 centimeters), take a small jar for canning, suspend the rod in the center and the strip on the side, pour in drain cleaner, you’ll get 1.2 to 1.4 volts DC. 10 of those connected to an inverter will give you 120 VAC at 0.5 amps. Do NOT keep them in the same area you live in however, the fumes will burn your lungs. Just something I learned in chem class in high school. You’d have to top-up the jars every few days, however. Any type of acid will work, even salt water. I think the teacher was a survivalist…

nbaldbiz

Scheffler, Hovland and Conners Share the Lead at P.G.A. Championship

Jordan Spieth, who needs a victory at Oak Hill to complete the career Grand Slam, and Justin Thomas, who won last year’s tournament, just made the cut at five over.

Give this article

Latest Comics

#443. 425 – Scowls And Smiles

53 Aug 21, 2019

#442. 424 – Oath And Displeasure

54 Aug 14, 2019

#441. 423 – Passing Judgment

49 Jul 31, 2019

#440. 422 – Mort Circuit

51 Jul 10, 2019

#439. 421 – Authentic Personnel Only

51 Jul 03, 2019

#438. 420 – Licensed To Shill

56 Jun 26, 2019

#437. EPISODE EIGHTEEN

64 Jun 24, 2019

#436. 419 – The Doctor Is In (END OF EPISODE 17)

52 Jun 05, 2019

#435. 418 – Making Huachucas Cry

48 May 29, 2019

#434. 417 – Need Aid? Grenade!

51 May 22, 2019

#433. 416 – Secs And Violence

45 May 15, 2019

#432. 415 – Thudding Optimism

51 May 08, 2019

#431. 414 – Gun Control

48 May 01, 2019

#430. 413 – AK O.K.

49 Apr 24, 2019

#429. 412 – Apology Deflected

48 Apr 17, 2019

#428. 411 – Nope A Dope

49 Apr 10, 2019

#427. 410 – All Downhill From Here

50 Mar 20, 2019

#426. 409 – And Don’t Call Her Shirley

50 Mar 13, 2019

#425. 408 – Watching The Huachers

51 Mar 06, 2019

#424. 407 – Talk To The Ranch Hand

51 Feb 27, 2019

Latest Chapters

Episode 22

Episode 21

Episode 20

Episode 19

Episode 18

Episode 17

541 – Graverobbers

WonderCon 2025 is coming soon, so the next comic is planned for April 9th.

In the meantime, relevant previousness for this week's page:

https://www.zombieranchcomic.com/comic/223-surrounded-by-film-end-of-episode-9/

https://www.zombieranchcomic.com/comic/483-solar-systems/

The cat is both alive and dead…

Calendar

BlueSky Latest Posts

Writer’s Blog Archives