Cart

Product categories

Support Us!

If you like what I do please support us on Ko-fi or Patreon.

Follow Us!

Join Our Newsletter!

Vote For Us!

Login

Polls

Events

-

Pasadena Comic Con

Dates: May 24

Location: Pasadena Convention Center, 300 E Green St, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA ( MAP)Details:We will be at the Pasadena Comic Con on January 26th. See some of you there for this one day event!

Purchase tickets online at here: https://www.tixr.com/groups/pcc/events/pasadenacomiccon-pasadena-comic-con-2025-115248

-

San Diego Comic Con: SP-N7

Dates: Jul 23 - 27

Location: San Diego Convention Center, 111 Harbor Dr, San Diego, CA 92101, USA ( MAP)Details:Clint & Dawn Wolf will be at San Diego Comic Con, as Lab Reject Studios. We will be at booth N7 in Small Press.

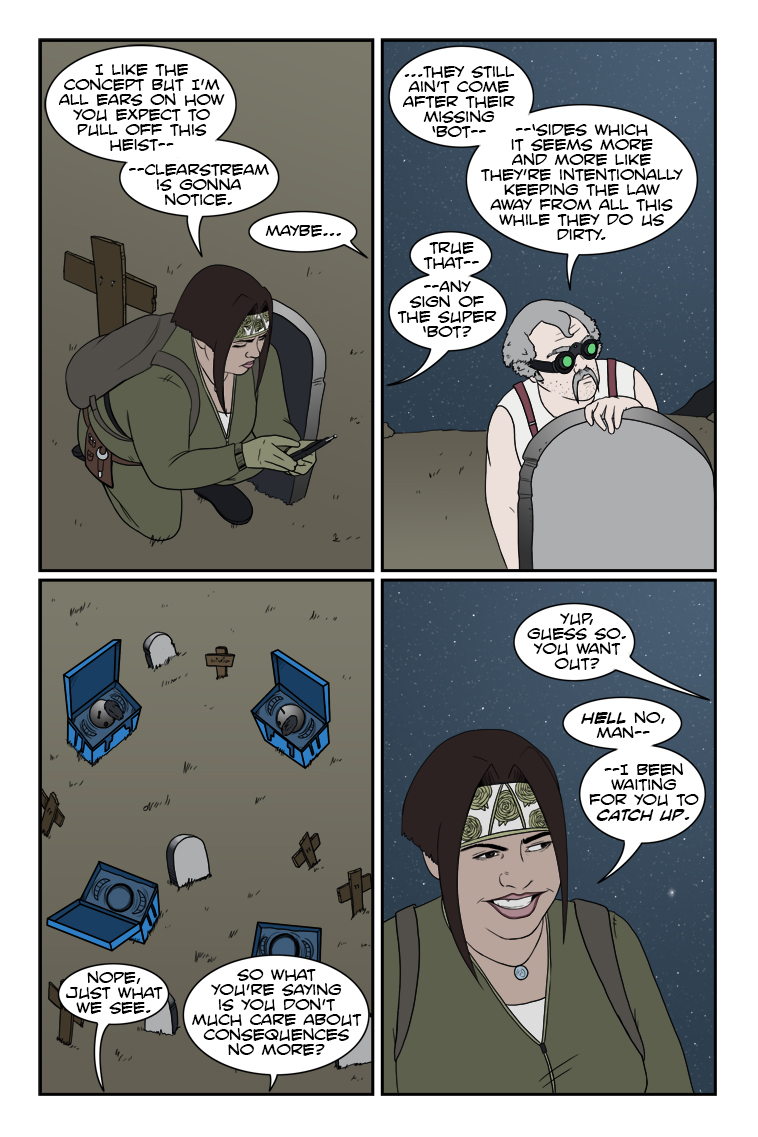

9 thoughts on “542 – Catching Up”

Keith

Some friction, but yeah. IRL, I’d like these two…they should have kids. 😉

Dawn

I might have to draw out what their kid would look like. First thought is that their kid would look like Ongo Gablogian from “It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia”

Scarsdale

He’s pushing 60, she’s maybe 30, more likely less. Chuck is most likely shooting blanks, and besides, he’s talking to her like a baby sister than a love interest.

Keith

Up in these hills, sometimes family is all y’gots. 😉

ConcordBob

It is really hard to have a favorite character, as there are so many good ones. But I think Rosa is my favorite. Chuck is a good accomplice in sneaking work, but not much for romance. Uugh.

Otaku

I mean, if they don’t have at least an inkling of what’s going down, I’m actually disappointed in Clearstream. If anything, I’m starting to wonder if they caught on and realized “Wait, we can use this.”

Because of course they can. 😉

Dr. Norman (not a real doctor)

I’m way ahead of you – I’ve been waiting for you to catch up. From November 2020:

I would hope for nothing less – her and Chuck have the potential for a great deal of positive mischief.

Speaking of which, I received the email notifying me that my order for the NSFW “Chuck and Rosa Finally Do It” (age verification required) limited edition hardcover is going to be delayed due to the pandemic. I think it’s really cool that you’ll be adding some additional stretch goal goodies when it ships – thanks for all your story and art.

As for the inscription, ” We owe it all to you ” will be sufficient.

Crazyman

Partners in crime! 😈

TKG

A crime so perfect she went full on wall-eye!

Latest Comics

#4. 03 – A Not-so-pale Horse

60 Oct 14, 2009

#3. 02 – Saddle Up!

49 Oct 07, 2009

#2. 01 – Lights! Camera! Action!

74 Oct 02, 2009

#1. EPISODE ONE

52 Sep 24, 2009

Latest Chapters

Episode 22

Episode 21

Episode 20

Episode 19

Episode 18

Episode 17

542 – Catching Up

Now you're getting the idea, Chuck!

Static on the frequency.

Calendar

BlueSky Latest Posts

Writer’s Blog Archives